what assumptions are necessary to prevent indifference curves from crossing?

Module 1: Preferences and Indifference Curves

The Policy Question: Is a Tax Credit on Hybrid Motorcar Purchases the Regime's Best Choice to Reduce Fuel Consumption and Carbon Emissions?

The U.Due south. government, concerned nearly the dependence on imported foreign oil and the release of carbon into the atmosphere, has enacted policies where consumers can receive substantial tax credits toward the purchase of certain models of all-electric and hybrid cars.

This credit may seem like a skilful policy choice only it is a plush one, it takes away resources that could exist spent on other government policies, and it is not the only approach to decreasing carbon emissions and dependency on fossil fuels. So how practice we decide which policy is best?

Suppose that this tax credit is wildly successful and doubles the average fuel economy of all cars on U.S. roads (this is clearly not realistic but useful for our subsequent discussions). What do y'all recollect would happen to the fuel consumption of all U.Due south. motorists? Should the government expect fuel consumption and carbon emissions of U.S. cars to subtract by half in response?

The answers to these questions are critical when choosing among the policy alternatives. In other words, is offering a subsidy to consumers the nigh effective way to meet the policy goals of decreased dependency on strange oil and carbon emissions? Are there more than efficient—that is, less expensive–means to achieve these goals? The ability to predict with some accuracy the response of consumers to this policy is vital to determining the merits of the policy before millions of federal dollars are spent.

Consumption decisions, such as how much motorcar fuel to consume, come up fundamentally frompreferences – our likes and dislikes. Man decision making, driven by our preferences, is at the cadre of economic theory. Since we can't consume everything our hearts desire, we take to make choices and those choices are based on our preferences. Choosing based on likes and dislikes does non mean that we are selfish–our preferences may include charitable giving and the happiness of others.

In this module, we will study preferences in economic science.

1.i Fundamental Assumptions about Individual Preferences

Learning Objective ane.1: List and explain the three fundamental assumptions well-nigh preferences.

1.2 Graphing Preferences with Indifference Curves

Learning Objective ane.2: Ascertain and describe an indifference curve.

1.3 Properties of Indifference Curves

Learning Objective ane.3: Relate the properties of indifference curves to assumptions nearly preference

1.4 Marginal Rate of Substitution

Learning Objective 1.4: Define marginal rate of substitution.

1.v Perfect Complements and Perfect Substitutes

Learning Objective one.5: Use indifference curves to illustrate perfect complements and perfect substitutes.

1.6 Policy Case: The Hybrid Car Taxation Credit and Consumer Preference

Learning Objective 1.half dozen: Apply indifference curves to the policy of a hybrid machine taxation credit.

one.1 Key Assumptions about Individual Preferences

Learning Objective one.one: List and explain the three fundamental assumptions nigh preferences.

To build a model that tin predict choices when variables change, we need to make some assumptions about the preferences that drive consumer choices.

Economics makes three assumptions nigh preferences that are the most basic building blocks of our theory of consumer choice.

To introduce these it is useful to think of collections or bundles of goods. To simplify, permit's identify two bundles, A andB. The fashion nosotros recall of preferences always boils downward to comparison 2 bundles. Even if nosotros are choosing amidst three or more bundles, we tin can always proceed by comparing pairs and eliminating the lesser bundle until we are left with our choice.

When we call something a proficient, we hateful exactly that – something that a consumer likes and enjoys consuming. Something that a consumer might not like we call a bad. The fewer bads consumed, the happier a consumer is. To keep things simple, nosotros volition focus merely on goods, but it is easy to incorporate bads into the same framework by considering their absence – the fewer the bads the ameliorate.

The three central assumptions about preferences are:

- Abyss: We say preferences are complete when a consumer can ever say one of the post-obit about ii bundles: A is preferred to B, B is preferred to A or A is equally skilful as B

- Transitivity:We say preferences aretransitiveif they are internally consequent: if A is preferred to B and B is preferred to C, then it must be that A is preferred to C.

- More is Meliorate: If bundle A represents more of at least i skilful, and no less of any other skilful, than bundle B, then A is preferred to B.

The most important results of our model of consumer behavior concur when we only presume completeness and transitivity, but life is much easier if we assume more is better equally well. If we assume costless disposal (we tin become rid of actress goods at no cost) the assumption that more is better seems reasonable. It is certainly the instance that more is not worse in that situation and so to go on things simple we'll maintain the standard assumption that we adopt more of a good to less.

Our model works well when these assumptions are valid, which seems to be most of the time in most situations. However, sometimes these assumptions practice not use. For case, in order to have complete and transitive preferences, nosotros must know something almost the goods in the parcel. Imagine an American who does not speak Hindi entering an Indian restaurant where the menu is entirely in Hindi. Without the aid of translation, the customer cannot human action as economic theory would predict.

i.two Graphing Preferences with Indifference Curves

Learning Objective 1.2: Define and draw an indifference curve.

Individual preferences, given the basic assumptions, can exist represented using something chosen indifference curves. An indifference curveis a graph of all of the combinations of bundles that a consumer prefers equally. In other words, the consumer would be simply as happy consuming whatever of them. Representing preferences graphically is a groovy mode to empathise both preferences and how the consumer choice model works – so it is worth mastering them early on in your study of microeconomics.

Bundles can contain many goods, but to simplify, we will consider merely pairs of appurtenances. At kickoff, this may seem impossibly restrictive but information technology turns out that we don't really lose generality in and so doing. We can always consider one good in the pair to be, collectively, all other consumption goods. What the ii-good restriction does so well is to help us see the tradeoffs in consuming more of i adept and less of another.

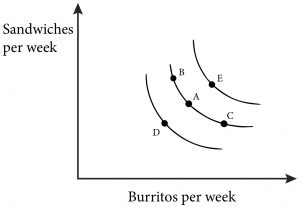

Figure 1.ii.1Bundles and Indifference Curves

Effigy 1.2.1 is a graph with two goods on the axes: the weekly consumption of burritos and the weekly consumption of sandwiches for a college student. In the center of the graph is indicate A, which represents a parcel of both burritos (read from the horizontal centrality) and sandwiches (read from the vertical axis).

At present we can ask what bundles are better, worse, or the same in terms of satisfaction to this college educatee. Clearly bundles that contain less of both appurtenances, like packet D, are worse than A, B or C considering they violate the more is a improve assumption. As clear is that bundles that contain more of both goods, similar parcel E, are better than A, B, C, and D because they satisfy the more is improve assumption.

To create an indifference curve we want to place bundles that this college student is indifferent about consuming. If a bundle has more burritos the student would accept to have fewer sandwiches and vice versa. Past finding all the bundles that are just as skilful as A, like B and C, and connecting them with a line, we create an indifference curvelike the one in the eye.

Observe that Effigy i.2.1 includes several indifference curves. Each curve represents a different level of overall satisfaction that the student can achieve via burrito/sandwich bundles. A curve further out from the origin represents a higher level of satisfaction than a bend closer to the origin.

Notice likewise that these curves share a number of characteristics: they gradient downward, they do non cross and they are all bowed in. Nosotros explore these backdrop in more particular in the side by side section.

1.3 Properties of Indifference Curves

Learning Objective one.iii: Relate the properties of indifference curves to assumptions nearly preference.

As introduced in Section 1.2, indifference curves have three key properties:

- they aredown sloping

- they do not cross

- they are bowed in(a non-technical way of saying they are convex to the origin).

For simplicity and clarity, from here on we will depict preferences that pb to indifference curves with these three properties as standard preferences. This will be our default assumption – that consumers take standard preferences unless otherwise noted. As we will come across in this module, in that location are other types of preferences that are mutual as well and we will continue to study both the standard type and the other types as we progress through the material.

To empathise the commencement two properties, it's useful to remember about what happen if they were not truthful.

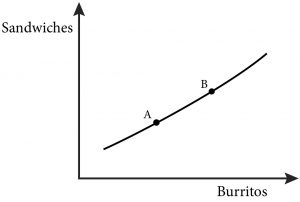

Figure i.3.iUpward Sloping Indifference Curves Violate the More than-is-Amend Assumption

Call up about indifference curves that slope upwardly as in figure 1.3.one. In this case nosotros have two bundles on the same indifference curve, A and B but B has more of both burritos and sandwiches than does A. Then this violates the assumption of more is meliorate. More is meliorate implies indifference curves are down sloping.

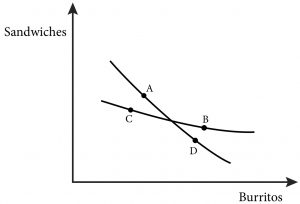

Figure ane.iii.2: Crossing Indifference Curves Violate the Transitivity Assumption

Similarly, consider Effigy 1.3.2. In this figure there are two indifference curves that cross. Now consider bundle A on i of the indifference curves. It represents more than of both goods than bundle C that lies on the other indifference bend. Considering the packet B lies on the same indifference curve every bit parcel C the two bundles should be every bit preferred and therefore A should be preferred to B and C. B besides represents more of both goods than package D and therefore B should be preferred to D. Notwithstanding D is on the same indifference curve every bit A, so B should be preferred to A. Since A can't be preferred to B and B preferred to A at the same fourth dimension, this is a violation of our assumptions of transitivity and more than is better. Transitivity and more than is improve imply that indifference curves practice not cantankerous.

Now we come to the third property: indifference curves bow in. This property comes from a fourth assumption about preferences, which we can add together to the assumptions discussed in Section 1.1:

- Consumers like diversity.

The assumption that consumers prefer diverseness is not necessary, but still applies in many situations. For example, well-nigh consumers would probably adopt to eat both sandwiches and burritos during a week and non simply one or the other (remember this is for consumers who consider them both goods – who like them). In fact, if you had only sandwiches to eat for a week, yous'd probably be willing to give up a lot of sandwiches for a few burritos and vice versa. Whereas if you had reasonably equal amounts of both yous'd be willing to trade one for the other but at closer to 1 to 1 ratios. Discover that if we graph this we naturally go bowed in indifference curves, as shown in Effigy 1.3.iii. Preference for variety implies indifference curves are bowed in.

Figure i.3.3Preference for Variety Ways that Indifference Curves are Bowed In.

Call up these three key points about preferences and indifference curves:

- More is better implies indifference curves are downward sloping.

- Transitivity and more is ameliorate imply indifference curves do not cross.

- Preference for diverseness implies indifference curves are bowed in.

one.4 Marginal Rate of Substitution

Learning Objective 1.4: Ascertain marginal charge per unit of substitution.

From now on we will presume that consumers like multifariousness and that indifference curves are bowed in. However, it is worth because examples on either extreme: perfect substitutes and perfect complements.

When we move along an indifference bend we can think of a consumer substituting ane good for some other. Two bundles on the aforementioned indifference curve, which represent the aforementioned satisfaction from consumption, accept one affair in common: they stand for more of one good and less of the other. This makes sense given our assumption of 'more is better'; if more of 1 practiced makes y'all amend off, then you must have less of the other practiced in order to maintain the same level of satisfaction.

In economic science we accept a more technical style of expressing this tradeoff: the marginal rate of substitution. The marginal charge per unit of substitution (MRS)is the corporeality of one skillful a consumer is willing to give up to get one more unit of another proficient and maintain the same level of satisfaction. This is one of the most important concepts in economic science considering it is critical to understanding consumer choice.

Mathematically, we express the marginal charge per unit of commutation for two generic goods like this:

[latex]MRS=\frac{\Delta A}{\Delta B}[/latex]

where Δ indicates a change in the quantity of the good.

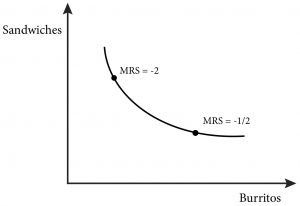

In the case of our student consuming burritos and sandwiches, the expression would be:

[latex]MRS=\frac{\Delta Sandwiches }{\Delta Burritos}[/latex]

For example suppose at his current consumption bundle, 5 burritos and iv sandwiches weekly, Luca is willing to give up ii burritos to get one more sandwich. Some other style of maxim the same thing is that Luca is indifferent between consuming five burritos and 4 sandwiches in a week or iii burritos and 5 sandwiches in a week. The MRS for Luca at that point is:

[latex]MRS=\frac{\Delta Sandwiches }{\Delta Burritos}=\frac{-2}{one}=-2[/latex]

Notation that the MRS is negative because it represents a tradeoff: more than sandwiches for fewer burritos.

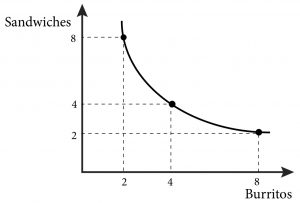

Effigy 1.four.ane illustrates the marginal charge per unit of substitution for burritos and sandwiches graphically.

Figure 1.four.aneMarginal charge per unit of substitution for burritos and sandwiches.

Discover that Effigy 1.iv.1 illustrates a change in the expert on the vertical axis (sandwiches) over the change in the good on the horizontal axis (burritos). This is the aforementioned as proverb the ascension over the run. From this word and graph, it should be articulate that the MRS is same equally the slope of the indifference curve at any given indicate along information technology.

1.5 Perfect Complements and Perfect Substitutes

Learning Objective i.5: Utilize indifference curves to illustrate perfect complements and perfect substitutes.

We accept at present studied the assumptions upon which our model of consumer behavior is built:

- abyss

- transitivity

- more than is better

- love of diverseness

We have too seen how these assumptions govern the properties of indifference curves.

It is worth taking a moment to think almost two other types of preference relations that are special cases but non uncommon: perfect complements and perfect substitutes.

Perfect Complements

Perfect complementsare goods that consumers want to consume only in fixed proportions.

Consider the case of an iPod Shuffle and earphones. An iPod Shuffle is useless without earphones and earphones are useless without an iPod Shuffle, but put them together and, voila, you take a portable stereo, which is worth quite a lot. An extra ready of earphones doesn't increase the usefulness of the iPod and an actress iPod doesn't increase the usefulness of the earphones. So these are things that we consume in a fixed proportion: one iPod goes with one set of earphones. We call such preference relations perfect complements.

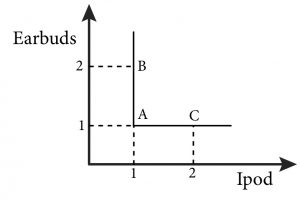

Effigy 1.5.1 illustrates the process of drawing indifference curves for perfect complements.

Figure 1.5.one: Indifference Curves for Goods that are Perfect Complements

In Figure 1.5.ane, when we start with a bundle of 1 iPod and one set of earbuds (as in packet A), what are the other bundles that are just every bit good to the consumer? Two sets of earbuds and one iPod is no better than ane set of earbuds and i iPod, so bundle B lies on the aforementioned indifference curve. The aforementioned is true for two iPods and one set of earbuds, every bit in bundle C. From this example, we can see that indifference curves for perfect complements have right angles.

Perfect Substitutes

Perfect substitutes are goods almost which consumers are indifferent as to which to consume.

That is, one unit of one good is merely as good as i unit of some other good. Both Morton and Diamond Crystal are brands of table salt. For most consumers, a teaspoon of i table salt is only as proficient as a teaspoon of the other regardless of the corporeality possessed by the consumer. We call goods like these perfect substitutes.

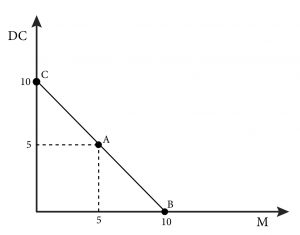

Cartoon indifference curves for perfect substitutes is straightforward as shown in Figure 1.five.2.

Effigy 1.5.2: Indifference Curves for Goods that are Perfect Substitutes

Packet A in Figure 1.five.2 contains 5 teaspoons of each blazon of salt. This is but as expert to the consumer as a bundle with ten teaspoons of Morton salt and zip teaspoons of Diamond Crystal as in bundle B. Information technology is too just as proficient as the x teaspoons of Diamond Crystal and zero teaspoons of Morton in bundle C.

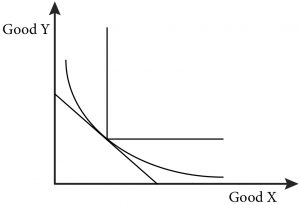

You tin think of perfect complements and perfect substitutes as polar extremes of preference relations. Figure ane.5.3 shows how a typical indifference curve lies betwixt perfect complements and perfect substitutes. You should empathise when graphically represented, that the indifference bend for well-behaved preferences lies between perfect complements and perfect substitutes.

Effigy 1.v.iii: The Human relationship between Indifference Curves for Well Behaved Preferences and Perfect Complements and Substitutes

ane.6 Policy Example: The Hybrid Car Taxation Credit and Consumer Preference

Learning Objective one.6: Apply indifference curves to the policy of a hybrid car taxation credit

The outcome of consumer preferences is key to the real-world policy question posed at the offset of this module.

Recall that we are assuming that the revenue enhancement credit will cause the boilerplate fuel economy of U.S. cars to double. So, from a consumer behavior perspective, one of the things we want to know in evaluating the policy is whether this improvement in gas mileage will cause an equivalent decrease in the demand for gasoline. In other words, the consumer conclusion is about the tradeoff of purchasing gasoline to travel in a car versus all of the other uses of the money spent on gas.

We tin apply the principle of preferences and the assumptions nosotros brand virtually them to this particular question by drawing indifference curves, as shown in Effigy 1.half dozen.1

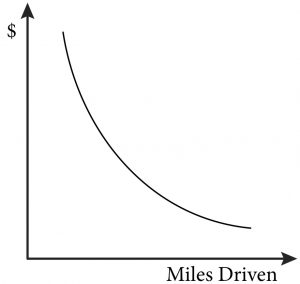

Figure one.vi.1: Indifference Bend for Miles Drives versus Money Spent on All Other Goods

We can label one axis of the indifference bend map "miles driven" and the other "money for other consumption." Doing so illustrates how circumscribed ourselves to only two dimensions is really not that confining at all. By considering the other centrality as money for all other purchases we are really looking at the general trade-off betwixt ane particular consumption good and everything else that a consumer could possibly consume.

So, what would our indifference curve wait like? As before it would be downwardly sloping – surely traveling more by car affords the consumer more freedom of movement and therefore more than consumption choices, both of which are a adept. The indifference curves would non cross for the aforementioned reasons discussed in section ane.3. But what about the principle of more is better? The point here is to once more call back about the principle of gratuitous disposal: as long every bit the power to drive more than miles is bang-up (and it is difficult to imagine how it could be) then more than miles are never worse.

The remaining question is whether the preference for multifariousness is a practiced supposition in this case. Information technology is helpful to consider the extremes: for those consumers who own cars, never driving any miles is probably not very practical. Besides spending one's entire income but on expenses relating to driving one'southward machine is unappealing. A good assumption, then, is that well-nigh people with a motorcar would prefer some combination of miles driven and other consumption to either extreme and we tin can describe our indifference curves equally convex to the origin.

Nosotros are not yet in a position to say much about the policy itself, just we have ane piece of the model we will utilize to analyze it. With this indifference curve we tin motility on to the other pieces of the model that we volition study in Modules 2, 3 and iv.

Exploring the Policy Question

- Suppose that a typical consumer is concerned about how his or her individual driving habits are negatively impacting the environment. How might such a modify in attitude change the shape of the consumer's indifference curves?

SUMMARY

Review: Topics and Related Learning Outcomes

ane.1 Cardinal Assumptions nigh Private Preferences

Learning Objective ane.1: Listing and explain the iii key assumptions about preferences.

i.two Graphing Preferences with Indifference Curves

Learning Objective 1.2: Define and depict an indifference curve.

1.iii Properties of Indifference Curves

Learning Objective i.three: Relate the properties of indifference curves to assumptions about preference.

1.4 Marginal Rate of Commutation

Learning Objective 1.four: Define marginal rate of commutation.

1.five Perfect Complements and Perfect Substitutes

Learning Objective 1.5: Use indifference curves to illustrate perfect complements and perfect substitutes.

1.six Policy Example: The Hybrid Motorcar Tax Credit and Consumer Preference

Learning Objective 1.six: Apply indifference curves to the policy of a hybrid car revenue enhancement credit

Learn: Key Terms and Graphs

Terms

Completeness

Transitivity

More is better

Indifference curve

Marginal rate of commutation (MRS)

Perfect complements

Perfect substitutes

Graphs

Indifference bend

Marginal rate of substitution

Perfect complements

Perfect substitutes

Equations

[latex]MRS=\frac{\Delta A}{\Delta B}[/latex]

Source: https://open.oregonstate.education/intermediatemicroeconomics/chapter/module-1/

0 Response to "what assumptions are necessary to prevent indifference curves from crossing?"

Postar um comentário